Absolute vs Relative Risk Calculator

This calculator helps you understand the real benefit of medical treatments by converting relative risk claims into absolute risk terms.

Example: A drug that reduces heart attack risk from 2% to 1% has a 50% relative risk reduction. However, the absolute risk reduction is only 1%, meaning you'd need to treat 100 people to prevent one heart attack.

Results

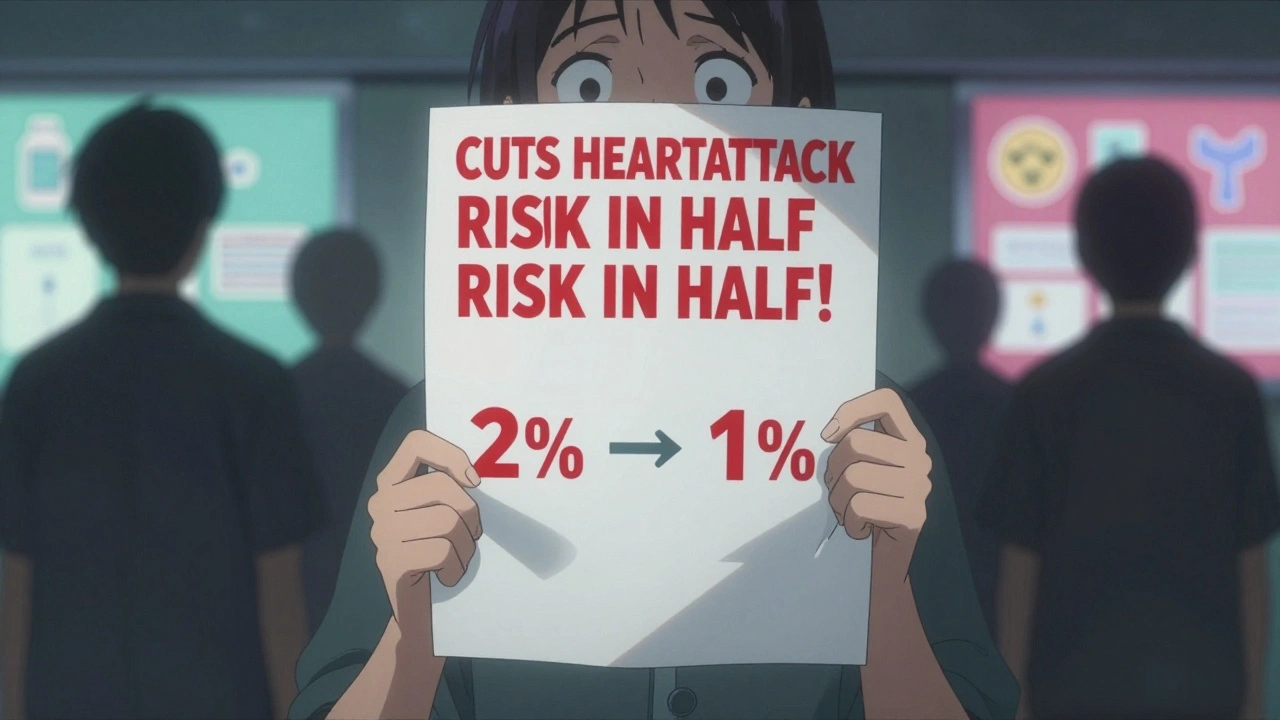

When a drug ad says it "cuts your risk of heart attack in half," you might think you’re avoiding a major health crisis. But what if your actual risk was only 2% to begin with? Cutting that in half means going from 2% to 1%-a 1 percentage point change. That’s not the same as saying half of all people will be saved. This confusion isn’t your fault. It’s built into how drug companies, doctors, and even news headlines report risk. The difference between absolute risk and relative risk isn’t just technical-it’s life-changing.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk is the real, plain number. It tells you how likely something is to happen to you, based on your situation. For example: if 1 in 1,000 people who take a certain drug develop a serious liver problem, that’s an absolute risk of 0.1%. If you’re one of those 1,000 people, your chance is 0.1%. No tricks. No math games. Just the truth.This is the number that matters most when you’re deciding whether to take a pill. If a side effect affects 1 in 10,000 people, that’s very rare. If it affects 1 in 10, you need to think hard. Absolute risk doesn’t lie. It doesn’t inflate. It just states the facts: how many people out of how many actually experience the effect.

Doctors use absolute risk to make real decisions. If a medication reduces your chance of stroke from 5% to 4%, that’s a 1% absolute risk reduction. It sounds small. But if you’re 70 and have high blood pressure, that 1% could mean avoiding a life-altering event. That’s why clinical guidelines always start with absolute risk.

What Relative Risk Can Hide

Relative risk is a ratio. It compares two groups: people who took the drug and people who didn’t. It’s calculated by dividing the risk in the treatment group by the risk in the control group. If the drug cuts your risk from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50%. That’s because 1% is half of 2%.That sounds impressive. And that’s exactly why drug ads love it.

Here’s the problem: relative risk doesn’t tell you the starting point. A 50% reduction sounds huge-until you learn the original risk was 0.002%. Then, the reduction is just 0.001%. That’s not life-saving. It’s barely noticeable. But if you only hear "50% reduction," you might think you’re avoiding a 50% chance of disaster. You’re not. You’re avoiding a 0.001% chance.

One famous example: a drug that reduces heart attack risk from 2% to 1% is advertised as cutting risk "in half." That’s technically true in relative terms. But it’s misleading in practice. The absolute benefit? One fewer heart attack per 100 people taking the drug. That’s meaningful for some. For others, it’s not worth the cost or side effects.

Why Drug Ads Use Relative Risk

Pharmaceutical companies know what works. Relative risk numbers are bigger. They look better. A 50% reduction sounds like a miracle. A 1% reduction sounds like a footnote.A 2021 study found that 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. used relative risk reduction without ever mentioning the absolute numbers. That’s not an accident. It’s strategy.

Consider this: a drug reduces the risk of a rare side effect from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000. The relative risk reduction is 90%. That’s a powerful number to put on a billboard. But the absolute risk reduction? Just 0.099%. That’s less than one in a thousand. For most people, that’s not worth worrying about. But if you only hear "90% reduction," you might think the drug is nearly eliminating the risk entirely.

On the flip side, side effects are often reported using relative risk too. If 20% of people on a new antidepressant get sexual dysfunction, and 8% on placebo do, that’s a 140% increase in relative risk. But the absolute difference? Just 12 percentage points. That’s still a real issue-but it’s not "most people will lose their sex drive." It’s about one in eight. That’s different.

What the Numbers Really Tell You

Here’s how to decode them side by side:- Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR): The actual drop in chance. Calculated as: Control Group Risk - Treatment Group Risk.

- Relative Risk Reduction (RRR): The percentage drop relative to the original risk. Calculated as: (ARR / Control Group Risk) × 100.

- Number Needed to Treat (NNT): How many people need to take the drug for one person to benefit. Calculated as: 1 / ARR.

Let’s say a cholesterol drug lowers your chance of heart attack from 5% to 4%. That’s:

- ARR = 1% (0.01)

- RRR = 20% (because 1% is 20% of 5%)

- NNT = 100 (because 1 / 0.01 = 100)

That means you’d need to give this drug to 100 people for one person to avoid a heart attack. The other 99 get no benefit-and might still deal with muscle pain, liver issues, or diabetes risk.

Compare that to a drug that drops heart attack risk from 10% to 5%. Same RRR: 50%. But now:

- ARR = 5%

- NNT = 20

That’s a much better deal. Four times more people benefit for the same cost. The relative risk looks the same-but the real-world impact is totally different.

What Patients Say

On Reddit’s r/medicine, a primary care doctor wrote: "I had a patient refuse statins because they read online that it ‘cuts heart attack risk in half.’ They thought it meant half the people wouldn’t have heart attacks. When I explained it was from 2% to 1%, they changed their mind."Another patient on Patient.info said: "The ad said ‘50% reduction in heart attacks.’ I thought it meant half the people taking it wouldn’t get heart attacks. I was terrified I’d be in the other half. Turns out, I was never at high risk to begin with. I felt manipulated."

These aren’t outliers. A 2019 JAMA study found that 60% of doctors couldn’t correctly convert a relative risk reduction into absolute terms. If even professionals struggle, it’s no wonder patients get confused.

How to Ask for the Real Numbers

You don’t need to be a statistician. Just ask these three questions:- "What’s my risk of this problem without the drug?"

- "What’s my risk with the drug?"

- "How many people like me need to take this for one to benefit?"

If your doctor gives you a relative risk number, ask: "Can you tell me the actual numbers?" Or: "What’s the absolute difference?"

Visual tools help too. Some clinics use "risk ladders"-a row of 100 tiny icons, with colored ones showing who gets the side effect or benefit. Seeing 2 red dots out of 100 for a side effect is clearer than hearing "a 100% increase."

One patient, Mrs. Smith, was about to refuse a blood pressure drug because the ad said it "reduced stroke risk by 30%." Her doctor showed her: "Without the drug, your chance of stroke in 5 years is 3%. With it, it’s 2.1%. That’s a 0.9% absolute drop. You’d need to treat 111 people like you to prevent one stroke." She agreed to try it-because she understood the trade-off.

What’s Changing

Regulators are catching on. The FDA issued draft guidance in January 2023 saying direct-to-consumer ads must clearly show both absolute and relative risk. The European Medicines Agency already requires both in patient leaflets. Some medical journals now require absolute risk data in published trials.Harvard Medical School added a required course on interpreting medical statistics in 2022. Why? Because 68% of graduating students couldn’t correctly interpret basic risk numbers.

But the biggest change isn’t in regulations-it’s in you. When you ask for absolute numbers, you force better communication. You push back against marketing tricks. You take control.

Final Rule: Always Start With Absolute Risk

Relative risk tells you how much the drug changes the odds. Absolute risk tells you whether those odds mattered in the first place.Don’t let a 50% reduction blind you. Ask: 50% of what? If the original risk was tiny, the benefit is tiny too. If the original risk was high, even a small absolute drop can be life-changing.

Side effects work the same way. A 200% increase in nausea sounds scary. But if it went from 2% to 6%, that’s 4 out of 100 people. Most won’t feel it. But if it went from 10% to 30%, that’s 1 in 3. That’s a real trade-off.

Numbers aren’t just data. They’re decisions. And you deserve to understand them.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is the actual chance of something happening-like a 2% chance of a heart attack. Relative risk compares two groups, like saying a drug cuts heart attack risk by 50%. That sounds big, but if your original risk was only 2%, the drug reduces it to 1%. The absolute change is small, even if the relative change is large.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Relative risk numbers are bigger and sound more impressive. A 50% reduction sounds better than a 1% reduction-even if they’re talking about the same thing. Drug companies use relative risk because it makes their product look more effective. But it doesn’t tell you whether the benefit matters for you personally.

How do I know if a drug’s side effects are serious?

Look for the absolute risk. If a side effect affects 1 in 100 people, that’s common. If it affects 1 in 10,000, it’s rare. Relative risk can make a rare side effect sound common. For example, a 200% increase from 0.5% to 1.5% sounds scary-but it’s still only 1.5 people out of 100. Always ask: "How many people actually experience this?"

What’s Number Needed to Treat (NNT)?

NNT tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit. If the NNT is 10, that means 10 people take it, and one person avoids the bad outcome. The other nine get no benefit-and might still have side effects. A low NNT (like 5) means the drug helps many people. A high NNT (like 100) means it helps very few.

Can I trust my doctor if they only give me relative risk?

You can still trust your doctor-but you should ask for more. Many doctors were never trained to explain absolute risk clearly. If they only give you percentages like "50% reduction," politely ask: "What’s my actual risk before and after the drug?" Good doctors welcome this. It shows you’re engaged in your care.

Emmanuel Peter

December 4, 2025 AT 17:58Ashley Elliott

December 5, 2025 AT 12:45michael booth

December 5, 2025 AT 18:15Alex Piddington

December 6, 2025 AT 19:17George Graham

December 8, 2025 AT 07:02John Filby

December 8, 2025 AT 18:52Elizabeth Crutchfield

December 9, 2025 AT 17:04Ben Choy

December 9, 2025 AT 23:18Ollie Newland

December 11, 2025 AT 00:05Rebecca Braatz

December 11, 2025 AT 13:56zac grant

December 11, 2025 AT 14:04Carolyn Ford

December 13, 2025 AT 10:17Heidi Thomas

December 15, 2025 AT 05:48