When you read a headline like "New Study Links Blood Pressure Drug to Heart Attacks", it’s natural to panic. You might stop taking your medicine. You might warn friends. But what if the study didn’t find what the headline says? What if the risk was tiny, or the dose was 10 times higher than what people actually take? Medication safety stories are everywhere - and most of them are misleading.

Why Media Reports on Drugs Are Often Wrong

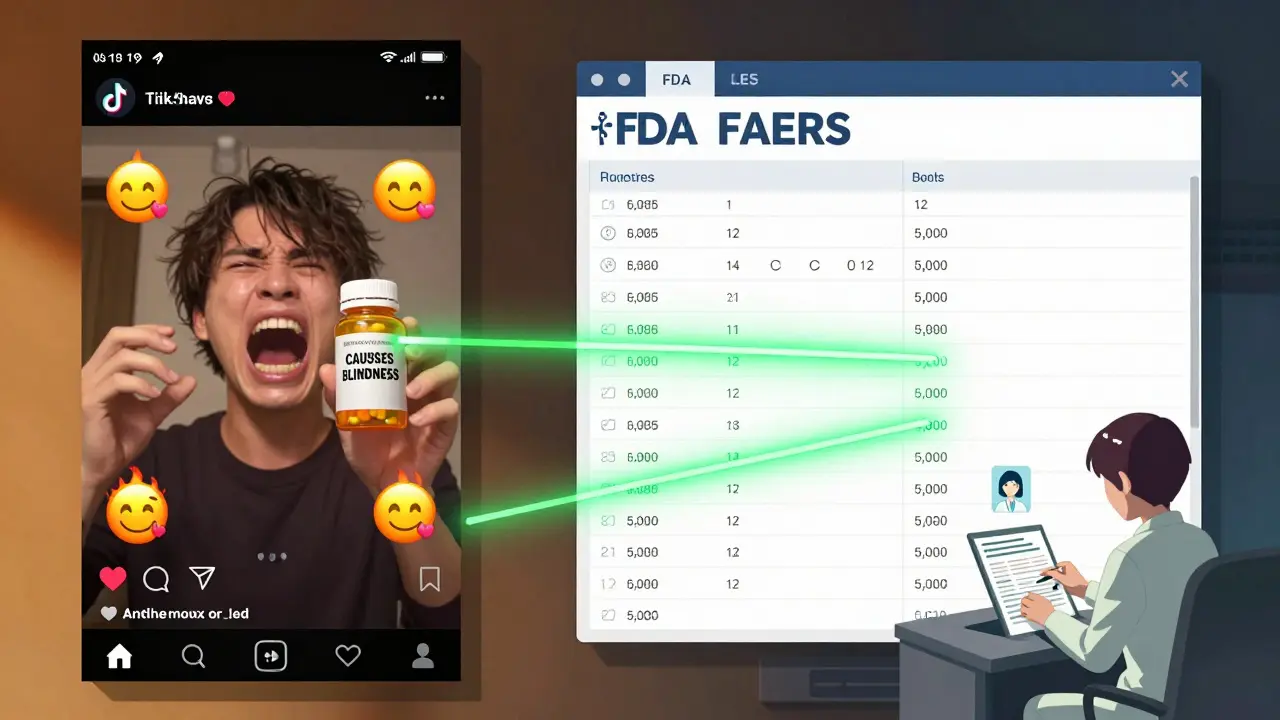

Media outlets don’t set out to mislead. But they’re under pressure to get clicks. A dramatic headline gets more views. A nuanced explanation about confidence intervals? Not so much. A 2021 study in JAMA Network Open looked at 127 news articles about medication safety. The results were startling: 79% didn’t explain the study’s limitations. 68% didn’t say what kind of error they were reporting. 54% left out how serious the harm actually was. That’s not reporting - that’s guesswork dressed up as science. One common mistake? Confusing medication errors with adverse drug reactions. A medication error is something that went wrong because of a human or system mistake - like a nurse giving the wrong dose. An adverse drug reaction is a harmful effect from a drug taken correctly. One is preventable. The other might not be. Yet most media reports treat them like the same thing. Another big issue: mixing up relative risk with absolute risk. Let’s say a study says a drug increases heart attack risk by 50%. Sounds scary, right? But if the original risk was 2 in 1,000, a 50% increase means it’s now 3 in 1,000. That’s not a public health crisis - it’s a small statistical shift. Only 38% of media reports include absolute risk numbers, according to a BMJ analysis. The rest leave you imagining the worst.What to Look for in a Credible Report

Not all drug safety stories are bad. But you need to know what to look for. Here’s what separates solid reporting from noise:- Does it name the study method? Was it a chart review? A trigger tool analysis? A spontaneous report from doctors? Each has limits. Chart reviews catch only 5-10% of actual errors. Trigger tools are more efficient but still miss things. Spontaneous reports (like those in FAERS) are full of noise - they don’t prove causation, just association.

- Does it define harm? Did they use a scale like the NCC MERP Index? That tells you if the error caused temporary harm, permanent injury, or death. If it just says “harmful,” skip it.

- Does it mention confounding factors? Did the study control for age, other meds, or pre-existing conditions? Only 35% of media reports do. If not, the results could be fake.

- Does it cite primary sources? Did they link to the FDA’s FAERS database, WHO’s Uppsala Monitoring Centre, or clinicaltrials.gov? Or did they just say “a new study found…”? If it’s not traceable, it’s not reliable.

- Does it explain limitations? Every study has them. Was the sample size small? Was it retrospective? Was it funded by a drug company? If the article skips this, it’s hiding something.

The Role of Official Databases

The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and the WHO’s Uppsala Monitoring Centre are the gold standards for collecting drug safety data. But they’re not what most people think. FAERS is a voluntary system. Anyone - doctors, patients, pharmacists - can report a problem. That’s good for catching rare side effects. But it’s terrible for figuring out how common those side effects are. A report doesn’t mean the drug caused the problem. It just means someone thought there might be a link. A 2021 study in Drug Safety found that 56% of media reports treated FAERS data as proof of danger. That’s wrong. FAERS data shows signals - not statistics. Think of it like smoke alarms. They go off for many reasons: burnt toast, steam, or fire. You don’t call the fire department every time one beeps. You check the source. If a report says “1,000 cases reported,” ask: “Reported to whom? Over what time? Compared to how many people took the drug?” If they can’t answer, the story isn’t trustworthy.

How Different Media Outlets Compare

Not all media is equal. A 2020 BMJ study compared 347 drug safety stories across outlets. Here’s what they found:| Media Type | Correctly Used Absolute Risk | Mentioned Study Limitations | Cited Primary Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Newspapers (NYT, Guardian, etc.) | 62% | 47% | 58% |

| Cable News | 38% | 18% | 29% |

| Digital-Only Platforms | 22% | 15% | 19% |

| Social Media (Instagram, TikTok) | 11% | 8% | 5% |

What Experts Say

Dr. Lucian Leape, who helped write the landmark 1999 report To Err is Human, says the biggest problem is conflating errors with reactions. “If you don’t know the difference, you can’t fix the problem,” he told a 2018 panel. His research showed 57% of media stories missed this distinction entirely. Dr. David Bates, who created the trigger tool method, warns that media often treats chart reviews as if they capture everything. “Those studies find maybe one in ten actual errors,” he says. “When you see a headline saying ‘1 in 5 patients harmed by this drug,’ it’s likely based on a chart review that missed 90% of cases.” The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) publishes a list of dangerous abbreviations - like “U” for units (which can look like “0”) or “QD” for daily (which can be mistaken for “QID”). If a media report talks about a medication error without mentioning these common pitfalls, it’s probably not talking to real pharmacists.

What You Should Do

You don’t need to be a scientist to spot bad reporting. Here’s your quick checklist:- Pause before reacting. Don’t stop your meds because of a headline. Talk to your doctor first.

- Find the original study. Search the drug name + “study” + “clinicaltrials.gov” or “PubMed.” Look for the journal name. Is it peer-reviewed?

- Check the numbers. Is there an absolute risk? What’s the baseline? Was the dose realistic?

- Look for the method. Was it a trigger tool? Chart review? Spontaneous report? Each has limits.

- Verify with official sources. Go to the FDA’s FAERS database. Search the drug. See how many reports there are - and how many are serious.

- Ask: Who benefits? Is the story pushing a new drug? A competing product? A supplement? Watch for hidden agendas.

When to Be Really Worried

Not every red flag means the drug is dangerous. But some signs are serious:- The report says the drug was “withdrawn” or “banned” - but it’s still on the market in the U.S. and EU. That’s false.

- It claims a drug causes “sudden death” without showing how many people actually died - or how many took it.

- It says “a new study proves…” but the study was published in a predatory journal or never peer-reviewed.

- It uses emotional language: “deadly,” “toxic,” “scandal,” “cover-up.” Real science avoids these words.

What’s Changing

There’s hope. The FDA launched the Sentinel Analytics Platform in 2023. It uses real-world data from millions of patients to track drug safety in near real-time. It’s not perfect, but it’s the most reliable source we have. The WHO is pushing for global standardization of medication error reporting. Right now, only 19.6% of countries use full standards. That’s changing - slowly. And AI is starting to help. A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open built a tool that scans drug safety articles and flags methodological flaws with 82% accuracy. It’s not public yet - but it’s coming. For now, your best tool is skepticism - and a few minutes of research. Don’t trust headlines. Don’t trust influencers. Don’t trust fear. Trust data. Trust context. Trust your pharmacist.Medication safety isn’t about avoiding risk. It’s about understanding it. And that starts with asking the right questions.

Chris Cantey

January 5, 2026 AT 10:33The real tragedy isn't the misleading headlines-it's that people stop taking life-saving meds because of them. I've seen it firsthand. My aunt stopped her beta-blocker after a viral TikTok claimed it caused heart failure. She ended up in the ER. The drug was fine. The fear wasn't.

Media doesn't lie. They just omit. And omission is its own kind of lie.

We treat medical information like entertainment. It's not. It's survival.

Abhishek Mondal

January 6, 2026 AT 12:12Let us not forget, however, that the very mechanism of peer-reviewed publication-ostensibly the gold standard-is itself compromised by publication bias, p-hacking, and institutional conflicts of interest; therefore, to place undue faith in clinicaltrials.gov or JAMA is, in fact, to engage in a form of epistemic complacency. The FAERS database, as you correctly note, is a noise-laden, voluntary reporting system-but so too is the entire edifice of modern pharmacovigilance, which operates under the illusion of objectivity while being structurally dependent on corporate-funded trials and regulatory capture.

Thus, your ‘checklist’ is not a solution-it is a distraction. The real question is: who benefits when we believe in ‘evidence’ at all?

Terri Gladden

January 8, 2026 AT 03:34Jennifer Glass

January 8, 2026 AT 19:58That Instagram post? I saw it too. I scrolled past it, then went back and clicked the link. It was a 2018 case report from a journal that got retracted. The drug? Different one. The patient? Had three other meds and a history of liver disease.

It’s not just misinformation-it’s misinformation with emotional hooks. We’re wired to react to fear. But we’re not wired to check sources.

I think the real fix isn’t better journalism-it’s better media literacy taught in high school. Like, before we’re allowed to drive, we should have to pass a ‘Don’t Panic Over Headlines’ test.

Joseph Snow

January 10, 2026 AT 09:41Of course the media gets it wrong. They’re controlled by the pharmaceutical industry. The FDA? A revolving door of ex-pharma executives. FAERS? A joke. They bury adverse events. You think they want you to know that 1 in 4 patients on these drugs develop irreversible kidney damage? No. They want you to keep taking them.

That ‘2021 JAMA study’? Funded by the American Medical Association, which gets millions from drug companies. You’re being manipulated to trust the system that’s lying to you.

My neighbor died after taking lisinopril. They called it ‘natural causes.’ I call it corporate murder.

melissa cucic

January 11, 2026 AT 15:38Thank you for this. So many people don’t realize that ‘50% increased risk’ can mean going from 0.2% to 0.3%. That’s not a crisis-it’s a footnote.

I work in pharmacy, and I see patients terrified of their meds because of headlines like ‘New Drug Linked to Stroke!’-and then I check the study: it was a 12-person case series, no control group, and the drug was given at 20x the standard dose.

People need to understand: correlation is not causation. And a single report in FAERS is not a verdict.

Also, please, please, please stop using ‘U’ for units. It’s a silent killer.

en Max

January 13, 2026 AT 07:54It is imperative that we recognize the epistemological limitations inherent in spontaneous reporting systems such as FAERS. While they serve a valuable function in signal detection, they are not designed for incidence estimation, nor are they statistically valid for causal inference.

Moreover, the conflation of medication error with adverse drug reaction represents a fundamental misclassification error, which undermines both clinical decision-making and public health communication.

It is therefore incumbent upon healthcare professionals and informed consumers alike to demand granular methodological transparency, and to reject narrative-driven reporting in favor of data-driven interpretation.

Furthermore, the absence of standardized terminology across media outlets exacerbates public confusion, and the proliferation of non-peer-reviewed content on social platforms constitutes a systemic failure of information governance.

Angie Rehe

January 15, 2026 AT 03:05Oh, so now you’re telling me to ‘check the original study’? Like I’m supposed to have time to dig through PubMed while my kid’s screaming and my dog’s throwing up? And who the hell are you to say I don’t know what ‘absolute risk’ means?

I’m not a scientist. I’m a single mom who takes her meds and tries not to die. If I see ‘drug linked to heart attack’ and I’m already on it, I’m gonna stop. And if you think that’s stupid, you haven’t lived.

Stop lecturing. Start making it easy to understand. Or at least don’t make me feel like an idiot for being scared.

Enrique González

January 16, 2026 AT 02:27My dad’s on warfarin. He’s 78. He reads every article about blood thinners. Last year, he saw a headline saying ‘New Study Shows Warfarin Causes Dementia.’ He stopped cold turkey. Went to the ER with a clot.

Turned out the study was about a new drug, not warfarin. The headline got it wrong. But the damage was done.

I’ve started printing out the original studies for him-just the abstracts and the risk numbers. We go over them together. It’s not perfect. But it’s better than letting the internet decide his health.

John Wilmerding

January 16, 2026 AT 14:10As a clinical pharmacist with over 18 years in patient education, I’ve seen the consequences of media-driven panic. The most dangerous myth isn’t that drugs are harmful-it’s that patients can self-diagnose risk from headlines.

I teach my patients to ask three questions: 1) What’s the actual risk? 2) What’s the alternative? 3) Who funded this? If they can’t answer #1, they shouldn’t act.

Also, if a report doesn’t mention the dose, it’s not trustworthy. A study showing toxicity at 1000mg doesn’t mean 5mg is dangerous.

And yes-FAERS is smoke, not fire. But it’s the only smoke alarm we’ve got. We just need to learn how to interpret it.

Peyton Feuer

January 16, 2026 AT 15:28bro i just stopped my antidepressant bc of a tiktok that said it made people 'emotionally numb forever'... turns out it was about a totally different drug and the person had bipolar and stopped cold turkey.

im sorry i was dumb. im going to my doc tomorrow. thanks for this post. i wish more people were like you.

josh plum

January 17, 2026 AT 20:57You think this is about bad journalism? No. This is about the Great Pharmaceutical Cover-Up. The FDA, WHO, CDC-they’re all in bed with Big Pharma. They suppress data. They bury deaths. They let drugs stay on the market for decades while people die.

That ‘Sentinel Platform’? A PR stunt. They’re using AI to *mask* the truth, not reveal it.

My cousin died on statins. They said ‘natural causes.’ I looked up the VAERS reports. 12,000 deaths. But they call it ‘coincidence.’

Don’t trust the system. Trust nothing. Question everything. Even this post.

Mandy Kowitz

January 19, 2026 AT 02:19Oh wow. So now we’re supposed to read JAMA like it’s a novel? Let me grab my monocle and my PhD in statistics before I take my blood pressure pill.

Meanwhile, my neighbor’s 80-year-old mom died from a stroke after reading this exact article and going back on her meds. So… congrats? You win the ‘Most Likely to Make People Dumb’ award.

Cassie Tynan

January 19, 2026 AT 15:40It’s not that the media gets it wrong. It’s that we *want* them to get it wrong.

We crave the drama. We want to believe there’s a conspiracy. We want to feel like we’re in the know when we ‘know’ the truth the system is hiding.

So they give us headlines. We give them clicks.

We’re not victims. We’re accomplices.

And that’s the real tragedy.

bob bob

January 19, 2026 AT 19:33I’ve been taking metformin for 12 years. I’ve seen 3 different headlines say it causes cancer, liver damage, and even ‘brain fog.’

I checked each one. None were true.

Now I just smile, read the study, and go about my day. My blood sugar’s stable. My doctor’s happy.

It’s not about being a genius. It’s about not letting fear run your life.

Also, my pharmacist gave me a sticker that says ‘Ask Before You Quit.’ I put it on my pill bottle. Best thing I ever did.

Chris Cantey

January 20, 2026 AT 00:05That’s the thing. We’re not supposed to be experts. But we’re supposed to be skeptical. Not paranoid. Skeptical.

My aunt didn’t die because of the drug. She died because she believed the worst without checking.

That’s the real side effect.

And it’s the one no one talks about.