Why Combining Insulin and Beta-Blockers Can Be Dangerous

If you're taking insulin for diabetes and also prescribed a beta-blocker for high blood pressure or heart disease, you might not realize you're at higher risk for a life-threatening drop in blood sugar-without any warning.

This isn't theoretical. Around 40% of people with type 1 diabetes develop hypoglycemia unawareness, meaning their body stops sending the usual signals-like shaking, racing heart, or sweating-when blood sugar plummets. Add beta-blockers into the mix, and those last few warning signs can vanish entirely. The result? A person can go from feeling fine to unconscious in minutes, with no time to react.

How Beta-Blockers Mask the Signs of Low Blood Sugar

Beta-blockers work by blocking adrenaline. That’s why they help lower heart rate and blood pressure. But adrenaline is also the body’s main alarm system for low blood sugar. When glucose drops, adrenaline triggers tremors, palpitations, and anxiety-your body’s way of saying, “Eat something now.”

Beta-blockers silence those alarms. Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol block both beta-1 and beta-2 receptors, wiping out nearly all physical warning signs. Even selective ones like metoprolol or atenolol reduce these signals significantly. The scary part? Your brain still gets starved of glucose. You just don’t feel it coming.

Here’s what’s often misunderstood: beta-blockers don’t stop sweating. That’s because sweat is controlled by a different pathway-acetylcholine, not adrenaline. So if you’re on a beta-blocker and start sweating unexpectedly, that’s your body’s last, critical cue. Learn to recognize it. Ignore it, and you’re playing Russian roulette with your brain.

The Hidden Metabolic Trap: Your Liver Can’t Help You

It’s not just about missing symptoms. Beta-blockers also interfere with your body’s ability to fix low blood sugar.

When glucose drops, your liver normally releases stored sugar (glycogen) to bring levels back up. Beta-2 receptors in the liver are key to this process. Block them, and your liver stays shut down. Muscle tissue also stops releasing glucose. So even if you eat a snack, your body can’t respond fast enough to recover.

This double whammy-no warning signs + no glucose rescue-is why hospital studies show patients on beta-blockers are 2.3 times more likely to have dangerous hypoglycemia. And if they’re on selective beta-blockers? The risk jumps even higher compared to carvedilol.

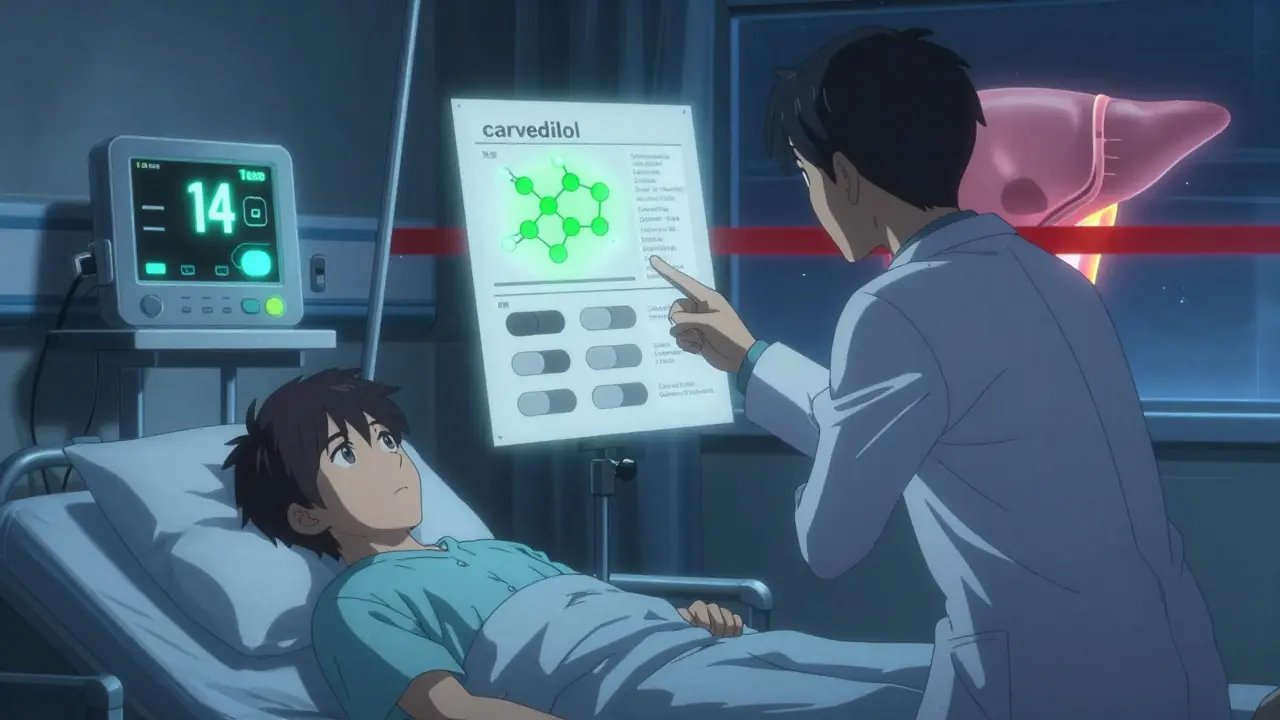

Not All Beta-Blockers Are Created Equal

Carvedilol is different. It’s not just a beta-blocker-it also blocks alpha receptors and has antioxidant properties. Studies show it’s less likely to mask hypoglycemia symptoms and doesn’t interfere with liver glucose release as much as metoprolol or atenolol.

In one major study, diabetic patients on carvedilol had a 17% lower rate of severe hypoglycemia than those on metoprolol. Hospital mortality linked to low blood sugar was also lower with carvedilol (odds ratio 0.78) compared to other beta-blockers (odds ratio 3.2).

That’s why guidelines now recommend carvedilol as the preferred beta-blocker for diabetic patients who need one. If you’re on propranolol or atenolol and have had low blood sugar episodes before, talk to your doctor about switching.

What Happens in the Hospital? A High-Risk Zone

Most dangerous hypoglycemia events happen in hospitals-especially in the first 24 hours after admission. Why? Stress, changed eating schedules, and insulin adjustments all collide with beta-blocker effects.

Research shows 68% of beta-blocker-related hypoglycemia in hospitals happens within the first day. That’s why the American Heart Association now recommends checking blood sugar every 2-4 hours for diabetic patients on beta-blockers during hospital stays.

But here’s the catch: many hospitals still don’t follow this. If you or a loved one is admitted, ask: “Are we checking my blood sugar every few hours?” Don’t assume it’s being done.

Continuous Glucose Monitors Are a Game Changer

Since 2018, use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among diabetic patients on beta-blockers has tripled. Why? Because when your body won’t warn you, technology must step in.

CGMs don’t just show your number-they alert you when it’s dropping, even while you’re asleep. Studies show they reduce severe hypoglycemia by 42% in this group. If you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker, a CGM isn’t a luxury. It’s a safety net.

Most insurance plans now cover CGMs for people on insulin. If yours doesn’t, ask your doctor to write a letter of medical necessity. The cost of one severe low-ER visit, ambulance, ICU stay-far outweighs the device.

What You Should Do Right Now

- If you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker: Ask your doctor if you’re on the safest type. Carvedilol is preferred. Avoid propranolol if you’ve had hypoglycemia before.

- Learn to recognize sweating: It’s your last natural warning. If you break into a cold sweat for no reason, check your blood sugar-don’t wait for shaking or dizziness.

- Get a CGM: If you don’t have one, insist on getting one. It’s the most effective way to prevent silent lows.

- Check your blood sugar more often: Especially before driving, exercising, or sleeping. Don’t wait to feel bad.

- Teach someone close to you: Make sure your partner, family, or coworker knows you’re at risk. Show them how to use glucagon. Many people don’t know glucagon exists anymore.

What About Long-Term Risk? The Evidence Is Mixed

Some studies, like the ADVANCE trial, found no increase in severe hypoglycemia over five years in outpatients on atenolol. That suggests the danger is mostly acute-during illness, hospitalization, or insulin changes.

But other data is clear: people on selective beta-blockers have a 28% higher risk of dying from hypoglycemia than those not on them. And while beta-blockers cut heart attack deaths by 25% in diabetics, that benefit can vanish if you have a severe low and can’t wake up.

This isn’t about avoiding beta-blockers. It’s about managing the risk. For many, the heart protection is worth it-but only if you take steps to stay safe.

The Future: Personalized Prescribing

Researchers are now looking at genetics to predict who’s most at risk. The DIAMOND trial (NCT04567890) is testing whether certain gene variants make some people far more likely to lose hypoglycemia awareness on beta-blockers.

Soon, we may be able to say: “Based on your DNA, carvedilol is safer for you.” Until then, stick with what we know works: better drugs, better monitoring, and better education.

Bottom Line: Don’t Assume You’ll Know When You’re Low

If you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker, your body has been silenced. You can’t trust your instincts anymore. That’s not weakness-it’s biology.

But you’re not powerless. You can choose the safest beta-blocker. You can wear a CGM. You can check your numbers more often. You can teach your loved ones how to help.

One silent low can end your life. But with the right tools and knowledge, you can live safely with both conditions. The choice isn’t between heart health and blood sugar control. It’s between ignorance and action.

Vince Nairn

January 7, 2026 AT 07:33Guess I'll start wearing a raincoat to bed just in case my liver decides to take a nap too.

Kamlesh Chauhan

January 8, 2026 AT 09:05Doctors prescribe beta blockers like candy

People die in hospitals because nobody checks sugar

And we wonder why healthcare is broke

Mina Murray

January 9, 2026 AT 16:08Rachel Steward

January 10, 2026 AT 02:23Jonathan Larson

January 10, 2026 AT 18:14Alex Danner

January 11, 2026 AT 11:19I didn’t know glucagon existed until my wife found the pen in the back of my drawer. It was expired. I cried.

Now I have a CGM. My wife knows how to use the glucagon. I check my sugar before I even touch my coffee. This isn’t fear. This is survival. Don’t wait for your body to scream. It’s already been silenced.

Katrina Morris

January 12, 2026 AT 04:41also i didnt know sweating was a sign? wow i always thought i was just hot lol

steve rumsford

January 13, 2026 AT 17:49my doc switched me from metoprolol and i haven’t had a scary low since

also side note: if your doctor doesn’t know what carvedilol is, find a new one

LALITA KUDIYA

January 15, 2026 AT 14:47beta blockers are everywhere here too

Poppy Newman

January 16, 2026 AT 14:07It’s like having a tiny doctor in my arm. And the alerts? Chef’s kiss. I even woke up once because it buzzed-no sweat, no shaking, just... ‘Hey, you’re dropping.’

Anthony Capunong

January 17, 2026 AT 13:13