When a doctor writes a prescription for a generic drug, they might think they’re doing the right thing-saving money, following guidelines, helping patients afford treatment. But in today’s legal landscape, that simple act can carry serious legal consequences. Physician liability for prescribing generics isn’t about intent. It’s about what happens when things go wrong, and who ends up being held responsible.

Why Prescribing Generics Can Put Doctors at Risk

In 2011 and 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court made two rulings that changed everything: PLIVA v. Mensing and Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett. These decisions said generic drug manufacturers can’t be sued for failing to update warning labels, even if a patient is seriously harmed. Why? Because federal law says generic makers must copy the brand-name label exactly-they can’t change it on their own. That left patients with nowhere to turn. No lawsuit against the maker. No compensation from the company that produced the drug. So where do they go? Often, straight to the doctor who wrote the prescription. This isn’t theoretical. Between 2014 and 2019, lawsuits targeting physicians over generic drug injuries rose by 37%. A patient develops toxic skin reactions after taking generic sulindac. Their lawyer looks at the chain of responsibility: the manufacturer can’t be touched. The pharmacist followed the law. That leaves the prescribing physician as the only viable target.How Liability Is Proven-The Three Legal Hurdles

To win a malpractice case against a doctor over a generic drug, the plaintiff must prove three things:- Duty: There was a doctor-patient relationship. This is almost always clear.

- Dereliction: The doctor failed to meet the standard of care. This is where it gets tricky. Did they warn the patient? Did they consider known risks? Did they document it?

- Direct cause: The medication directly caused the injury. This requires medical evidence linking the drug to the harm.

The State-by-State Patchwork of Rules

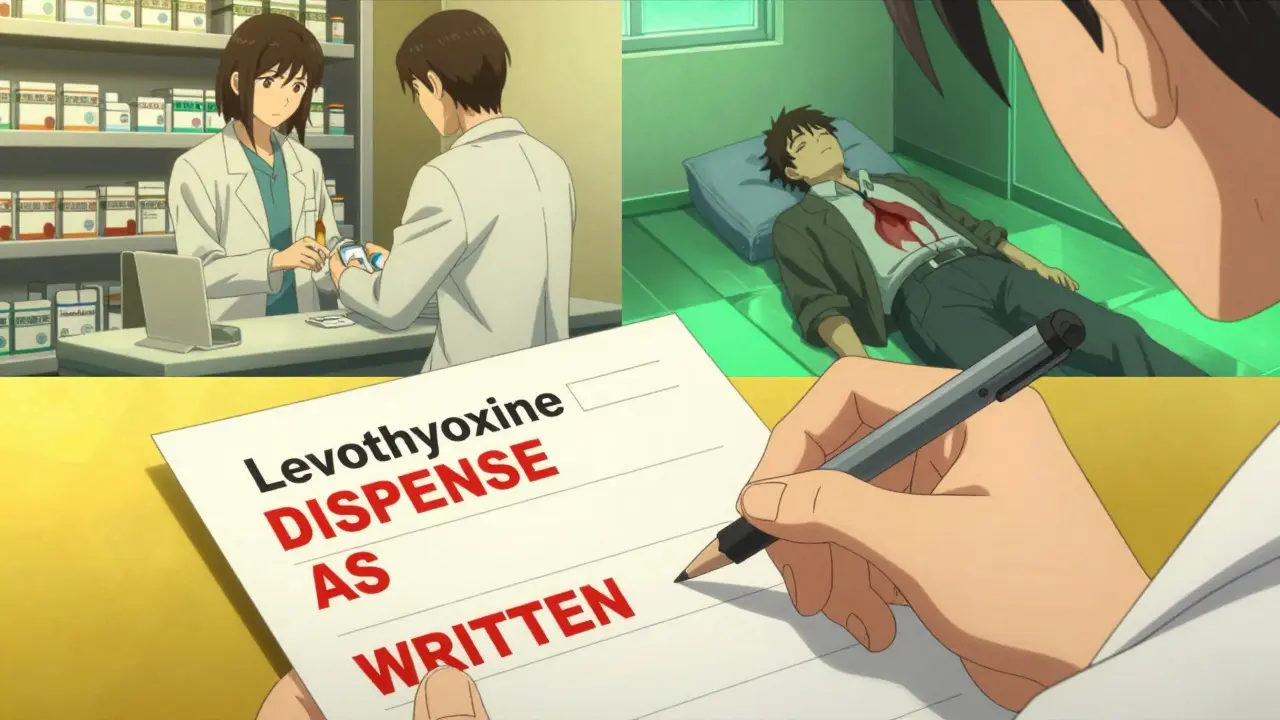

Forty-nine states let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a generic unless the doctor writes “dispense as written.” But here’s the catch: only 32 states require pharmacists to notify the doctor when they make the switch. In 17 states, the doctor might never know. That creates a dangerous blind spot. A patient gets a generic version of a narrow-therapeutic-index drug like warfarin or levothyroxine. The generic has slightly different absorption rates. The patient’s INR spikes. They bleed internally. The doctor didn’t know a substitution happened. They didn’t counsel the patient. Now they’re facing a lawsuit. Some states are trying to fix this. Illinois courts have ruled that generic manufacturers can be held liable if their drug is inherently dangerous and they refuse to update labeling. But in most states, federal preemption overrides state law. That means doctors in Texas, Florida, or Ohio face far greater exposure than those in Illinois.

What Doctors Are Doing to Protect Themselves

A 2022 survey of 1,200 physicians found that 68% feel more anxious about prescribing generics. Forty-two percent admit they sometimes choose brand-name drugs-even when cheaper options exist-just to avoid liability. Doctors are changing their habits:- They now write “dispense as written” on prescriptions for drugs like levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and seizure medications.

- They add detailed warnings to electronic health records: “Discussed risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with patient. Advised to seek immediate care if rash develops.”

- They’re spending 15-20 extra minutes per visit documenting every conversation about side effects.

Insurance Premiums Are Rising-And So Are Settlements

Professional liability insurers have noticed the trend. Premiums for primary care physicians rose 22.7% between 2013 and 2022. For those who routinely authorize substitutions without documentation, insurers now add a 7.3% surcharge. Settlements are climbing, too. The American College of Physicians recorded 47 malpractice claims related to generic drugs between 2016 and 2021. Twelve of them resulted in payouts averaging $327,500. One case involved a patient who developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome after a pharmacist substituted a generic anticonvulsant. The doctor had written “may substitute” and didn’t warn the patient about skin reactions. The settlement was $485,000.

What You Need to Do Right Now

If you prescribe medications, here’s what you need to do:- Know your high-risk drugs. Warfarin, levothyroxine, lithium, phenytoin, and some immunosuppressants have narrow therapeutic windows. Always write “dispense as written” on these.

- Document everything. Don’t say “medication discussed.” Say: “I explained that [drug] may cause dizziness, blurred vision, and nausea. I advised avoiding driving or operating heavy machinery until tolerance is established.”

- Use your EHR’s tools. If your system has a mandatory counseling field, fill it out. It’s your legal shield.

- Ask patients. “Have you taken this medication before? Did you have any side effects?” This isn’t just good medicine-it’s your defense.

- Stay updated. New safety warnings come out all the time. If the brand-name label changes, but the generic doesn’t, you’re the one who has to tell the patient.

The Bigger Picture

The system isn’t broken because of doctors. It’s broken because of a legal gap created by federal preemption. Generic manufacturers are shielded. Pharmacists follow the law. Patients get hurt. And doctors-facing the most direct relationship with the patient-are left holding the bag. The American Medical Association is pushing for state laws that require pharmacists to notify physicians within 24 hours when a substitution occurs. Eighteen states have introduced bills in 2023. But until federal law changes, the burden stays with you. The numbers don’t lie: 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are generics. That means nearly every doctor is affected. Ignoring this isn’t an option. Documenting carefully isn’t bureaucracy-it’s your protection.Can I be sued if I prescribe a generic drug and the patient gets hurt?

Yes. While generic manufacturers are protected by federal preemption, physicians can still be held liable if they failed to meet the standard of care-such as not warning about known side effects, not documenting patient counseling, or prescribing a high-risk drug without proper monitoring.

What’s the difference between prescribing a brand-name drug versus a generic in terms of liability?

Legally, the standard of care is the same. But if a patient is injured by a brand-name drug, they can sue the manufacturer. With generics, they can’t. That means the doctor becomes the primary target in lawsuits. The liability risk shifts entirely to the prescriber.

Do I have to write “dispense as written” on every prescription?

No-but you should for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, like warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain anti-seizure medications. In 32 states, this prevents pharmacists from substituting generics. For other drugs, it’s optional, but documenting counseling is still critical.

How detailed should my documentation be?

Be specific. Instead of “discussed side effects,” write: “I explained that [drug] may cause severe skin rash, dizziness, and liver toxicity. I advised reporting any new rash, yellowing of skin, or persistent nausea immediately.” Generic notes like “medication reviewed” offer no legal protection.

Is there any legal protection for doctors who follow all guidelines?

Following guidelines doesn’t guarantee immunity, but thorough documentation reduces liability exposure by up to 58%. Courts look for evidence that you acted reasonably. If you can show you warned the patient, documented the conversation, and chose the drug appropriately, you’re far less likely to lose a case.