When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing low blood sugar or weight gain feels like a win. That’s why SGLT2 inhibitors became so popular. But for many people, the side effects came out of nowhere - itching, burning, frequent urination - and turned into something far worse. These drugs work by pushing sugar out through your urine. Sounds harmless, right? But that sugar doesn’t just disappear. It stays in your urinary tract, turning it into a breeding ground for yeast and bacteria. And what starts as a mild irritation can quickly become a life-threatening infection.

How SGLT2 Inhibitors Work - and Why They Cause Infections

SGLT2 inhibitors - like dapagliflozin (Farxiga), empagliflozin (Jardiance), and canagliflozin (Invokana) - block a protein in your kidneys that normally reabsorbs glucose. Instead of being pulled back into your bloodstream, the extra sugar gets flushed out in your urine. That’s how they lower blood sugar. On average, patients lose 40 to 110 grams of glucose per day through urine. That’s about 160 to 440 calories - which is why many people lose 2 to 3 kilograms in the first few months.

But here’s the catch: yeast and bacteria love sugar. The moment glucose starts showing up in your urine, it creates the perfect environment for fungal overgrowth. That’s why genital yeast infections are one of the most common side effects. In clinical trials, 3% to 5% of people taking SGLT2 inhibitors developed a yeast infection, compared to just 1% to 2% on placebo. For women, that usually means vulvovaginal candidiasis - itching, swelling, thick white discharge. For men, it’s balanitis: redness, pain, and swelling around the head of the penis.

These infections don’t just appear randomly. They show up early - often within the first 3 months of starting the drug. And they’re not just annoying. Left untreated, they can spread.

The Bigger Risk: Urinary Tract Infections and Urosepsis

Genital infections are bad enough. But the real danger lies deeper - in the urinary tract itself.

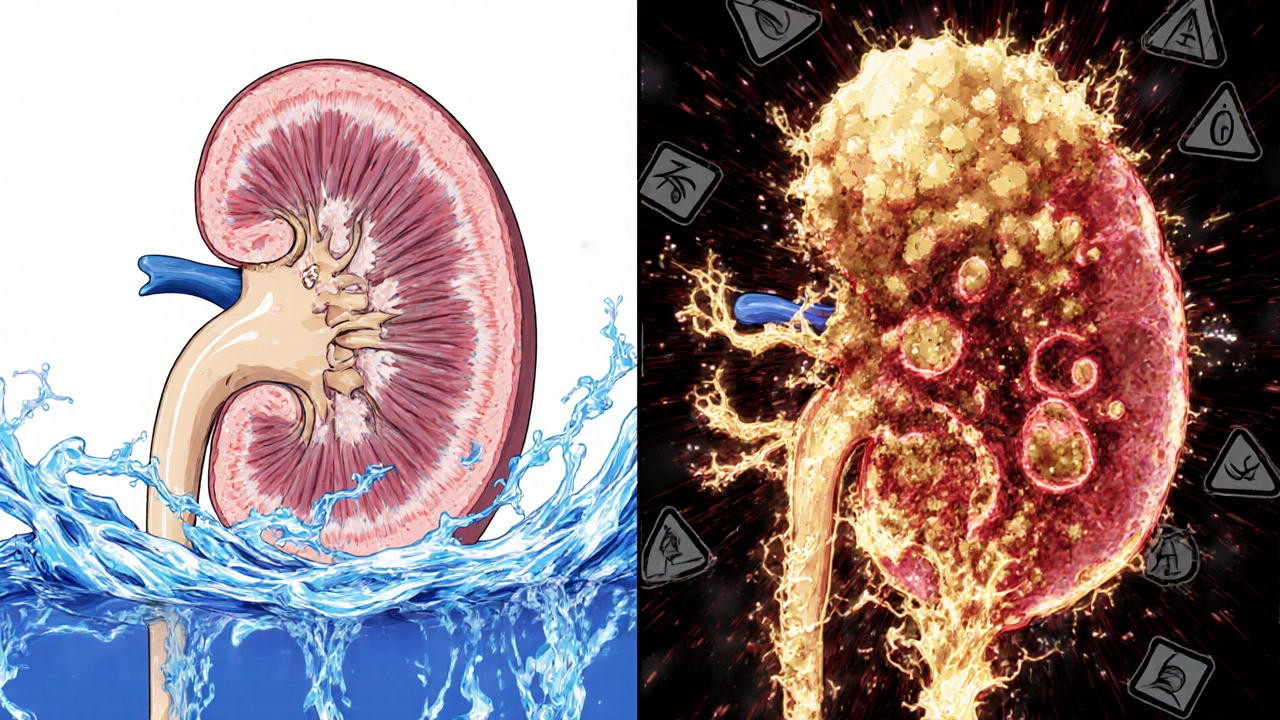

Studies show SGLT2 inhibitors increase the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) by nearly 80% compared to other diabetes medications like DPP-4 inhibitors or sulfonylureas. The FDA reviewed data from 2013 to 2014 and found 19 confirmed cases of urosepsis - a bloodstream infection triggered by a UTI - linked to these drugs. Ten of those cases involved canagliflozin, nine involved dapagliflozin. All 19 patients were hospitalized. Four needed intensive care. Two needed dialysis because their kidneys failed.

One case reported by the National Institutes of Health involved a 64-year-old woman with no prior history of UTIs. After starting dapagliflozin, she developed emphysematous pyelonephritis - a rare, gas-forming kidney infection. She needed 14 days of IV antibiotics. Months later, after restarting the drug, she got another infection - this time with a perinephric abscess. She had to have it drained. Her words: “I never had urinary problems before this medication, and now I’ve had two life-threatening infections.”

These aren’t outliers. The FDA’s database shows that 8 of the 19 urosepsis cases were caused by E. coli - a bacteria that normally lives in the gut but can turn deadly when it gets into the urinary system. Hospital stays averaged 7.5 days. Some patients never fully recovered kidney function.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone on SGLT2 inhibitors gets infections. But certain people are far more vulnerable.

- Women - due to shorter urethras, they’re more prone to UTIs and yeast infections.

- People over 65 - immune systems slow down with age.

- Those with a history of recurrent UTIs or yeast infections - if it’s happened before, it’s likely to happen again.

- People with poor hygiene, urinary retention, or catheter use - anything that traps urine increases risk.

- Patients with HbA1c above 8.5% - higher sugar levels in urine mean more fuel for microbes.

- Those with kidney disease (eGFR below 60) - the drug’s effect is stronger, so more sugar ends up in urine.

A 2024 study in Diabetes Care created a simple 5-point risk score. If you have three or more of these factors, your risk of a serious UTI jumps to over 15%. That’s not a small chance - it’s a red flag.

Fournier’s Gangrene: The Rare But Deadly Complication

Then there’s Fournier’s gangrene - a rare, fast-moving necrotizing infection of the genitals and perineum. It’s not common - only about 1 in 10,000 users - but it kills. The European Medicines Agency added a warning for it in 2016. It starts with pain or swelling near the genitals, then spreads. Skin turns black. Fever spikes. The infection eats through tissue. Surgery is often needed to remove dead skin. Some patients don’t survive.

One patient described waking up with severe pain in his groin. By morning, his scrotum was swollen and purple. He went to the ER and was rushed into surgery. “I thought I had a bad yeast infection,” he said. “It turned out I was dying.”

There’s no way to predict who will get it. But if you have any tenderness, redness, swelling, or fever in the genital area - especially with a fever above 100.4°F - you need to stop the drug and get to a hospital immediately.

How Doctors Are Changing Their Approach

When these drugs first came out, many doctors prescribed them freely. They were new, effective, and had low hypoglycemia risk. But after the FDA issued warnings in 2015 - and after more than 20% of patients in Sweden stopped taking them due to infections - attitudes changed.

Now, the American Diabetes Association says: “Assess history of recurrent urinary tract infections before initiating SGLT2 inhibitors.” If you’ve had more than two UTIs in the past year, or if you’re a woman with chronic yeast infections, your doctor should consider alternatives.

For patients with heart failure or existing cardiovascular disease, the benefits still outweigh the risks. Empagliflozin reduced major heart events by 14% in the EMPA-REG trial. Canagliflozin did the same in CANVAS. But for someone without heart disease - especially if they’re young, healthy, and just trying to control blood sugar - the infection risk may not be worth it.

Many endocrinologists now reserve SGLT2 inhibitors for second- or third-line use - after metformin, and only if the patient has heart or kidney disease. For others, DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists are safer choices.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

If you’re already on an SGLT2 inhibitor, don’t panic. But do take action.

- Hydrate. Drink plenty of water. It flushes sugar out faster and dilutes urine.

- Practice good hygiene. Wipe front to back. Change underwear daily. Avoid tight, synthetic fabrics. Don’t use scented soaps or douches.

- Watch for symptoms. Burning when you pee? Itching? Redness? Unusual discharge? Fever? Don’t wait. Call your doctor the same day.

- Consider cranberry. A 2023 FDA safety update noted that cranberry supplements reduced UTI rates by 29% in SGLT2 users. It’s not a cure, but it’s a low-risk protective step.

- Don’t restart after an infection. If you’ve had a serious UTI or yeast infection while on the drug, restarting it carries a high risk of recurrence. Talk to your doctor about switching.

One woman told her doctor, “I thought the itching was just from stress.” She waited two weeks. By then, the infection had spread to her bladder. She spent 10 days in the hospital. “I wish I’d known it wasn’t normal,” she said.

Is There a Future Without the Risk?

Drugmakers are working on solutions. New dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors are being tested - they may reduce urinary glucose spillage while still lowering blood sugar. Some are exploring extended-release forms or lower doses that minimize sugar excretion.

There’s also growing interest in personalized risk tools. A 2024 study developed a simple calculator based on age, sex, HbA1c, prior UTIs, and kidney function. It could help doctors decide who should avoid these drugs entirely.

For now, the message is clear: SGLT2 inhibitors are powerful tools - but they’re not for everyone. Their benefits are real, especially for people with heart or kidney disease. But the infections they cause are not minor inconveniences. They’re serious, sometimes fatal, and entirely preventable with awareness.

If you’re on one of these drugs, know the signs. Speak up. And if your doctor dismisses your symptoms as “just a yeast infection,” get a second opinion. Your body is telling you something important.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors cause yeast infections even if I’m not diabetic?

No. SGLT2 inhibitors are only approved for people with type 2 diabetes. They work by increasing glucose excretion in urine, which requires high blood sugar levels to be effective. In non-diabetics, blood glucose stays normal, so there’s little to no sugar in the urine - meaning the risk of yeast infections from these drugs doesn’t apply.

How long after starting SGLT2 inhibitors do infections usually appear?

Most genital infections show up within the first 1 to 3 months. Urinary tract infections can occur anytime, but the highest risk is in the first 6 months. Serious infections like urosepsis often appear between 30 and 90 days after starting the drug, though some cases have occurred as late as 9 months in.

Are there any SGLT2 inhibitors with lower infection risk?

All SGLT2 inhibitors carry the same mechanism-driven risk. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin all cause glucose to be excreted in urine - so they all increase infection risk similarly. There’s no “safer” option in this class. The difference lies in how your body responds, not the drug itself.

Should I stop taking my SGLT2 inhibitor if I get a yeast infection?

Don’t stop on your own. Treat the infection first - with antifungal creams or oral medication, as prescribed. If it clears up quickly and you have no other risk factors, your doctor may let you continue. But if it comes back, or if you have a UTI or fever, you need to discuss switching medications. Recurrent infections mean the drug is likely not safe for you.

Can cranberry supplements really help prevent UTIs on SGLT2 inhibitors?

Yes - and it’s backed by research. A 2023 FDA safety update cited a study showing cranberry supplements reduced UTI incidence by 29% in people taking SGLT2 inhibitors. It’s not a guaranteed shield, but it’s a simple, low-risk strategy that works for many. Look for products with at least 36 mg of proanthocyanidins per dose.

What are the alternatives to SGLT2 inhibitors if I’m at high risk for infections?

If you’re at high risk for infections, your doctor may switch you to a DPP-4 inhibitor (like sitagliptin or linagliptin) or a GLP-1 receptor agonist (like semaglutide or liraglutide). Both lower blood sugar without increasing glucose in urine. DPP-4 inhibitors have a similar safety profile to metformin. GLP-1 agonists also help with weight loss and heart protection - without the infection risk.

Nicole M

November 13, 2025 AT 13:53My doctor prescribed me Jardiance last year and I didn’t think twice until I started itching like crazy. Thought it was laundry detergent. Turned out it was yeast. Took two rounds of fluconazole. Never again.

Arpita Shukla

November 14, 2025 AT 02:08Okay but let’s be real - if your kidneys are dumping 100g of sugar a day into your bladder, you’re basically feeding a microbial buffet. No wonder infections spike. It’s not magic, it’s microbiology. And yet people act like this is some new discovery.

Alex Ramos

November 15, 2025 AT 11:03Just want to say - if you’re on one of these and feel even a hint of burning or weird discharge, DO NOT WAIT. I ignored mine for 10 days. Ended up with a UTI that turned into pyelonephritis. ER. IV antibiotics. Missed work for two weeks. This isn’t ‘just a yeast infection’ - it’s a red flag screaming at you.

Benjamin Stöffler

November 16, 2025 AT 04:27Let’s pause for a moment - we’re talking about a class of drugs that literally turn urine into a sugar-rich culture medium - and yet, somehow, we’re surprised when microbes thrive? We’ve engineered a biological paradox: we treat hyperglycemia by creating localized hyperglycemia in the urinary tract. Is this innovation? Or is it just metabolic irony?

Mark Rutkowski

November 16, 2025 AT 12:35There’s a quiet tragedy here - we celebrate these drugs for their weight loss and heart benefits, but we ignore the quiet suffering of people who wake up with burning skin and panic because their doctor says, ‘It’s just yeast.’ But yeast doesn’t turn your scrotum purple. Yeast doesn’t make you need dialysis. We’ve normalized danger because the numbers look good on paper. That’s not medicine - that’s math with a moral blind spot.

David Barry

November 18, 2025 AT 09:1290% of these posts are people who didn’t read the label. The FDA warnings have been out since 2015. The clinical trials showed 3-5% yeast infection rates. If you’re getting recurrent infections, it’s not the drug’s fault - it’s your failure to monitor. Stop blaming pharma and start taking responsibility.

Eve Miller

November 20, 2025 AT 08:29It’s not ‘just yeast’ - it’s a preventable, documented, and well-studied adverse event. If your doctor prescribes this without reviewing your UTI history, they’re negligent. Period. I’ve seen too many patients suffer because their provider treated this like a minor side effect. It’s not. It’s a systemic risk.

edgar popa

November 20, 2025 AT 20:32cranberry works. i took it daily after my first infection and havent had another in 8 months. no joke. also drink water like its your job.

Ryan Everhart

November 21, 2025 AT 06:27So let me get this straight - we’re giving people a drug that turns their pee into candy for bacteria, then telling them to drink more water and eat cranberries like it’s a yoga retreat? Meanwhile, the drug makers are making billions. And we’re supposed to be grateful?

manish kumar

November 22, 2025 AT 20:00I’m from India, and here, doctors still push these like they’re miracle pills. No one asks about your UTI history. No one checks your HbA1c before prescribing. I had a friend - 52, female, diabetic, had three yeast infections in a year - still got Farxiga prescribed. She ended up in ICU with urosepsis. Her husband had to sell his scooter to pay for the hospital. This isn’t science - it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

And yes, cranberry helps. We’ve been using neem and turmeric washes for generations. But no one wants to hear traditional remedies when there’s a patent to protect.

My advice? If you’re young, no heart disease, just trying to lose weight - stick with metformin. It’s older, cheaper, and doesn’t turn your private parts into a petri dish. The benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors are real - but they’re not worth the risk if you’re not in the high-risk group they were designed for.

And if your doctor says, ‘It’s just a yeast infection,’ ask them: ‘How many patients have you seen with Fournier’s gangrene?’ If they can’t answer - get a new doctor.

Amie Wilde

November 23, 2025 AT 19:20i got the infection after 6 weeks. stopped the drug. done. no regrets.

Alyssa Lopez

November 24, 2025 AT 10:12Why are we even debating this? The FDA said it. The data says it. People are getting dialysis because they took a pill that makes their pee sweet. If you’re not a cardio patient, you shouldn’t be on it. Period. Stop being lazy and switch to a GLP-1. They work better anyway.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 25, 2025 AT 18:24Let’s be honest - the real issue is that pharma markets these as weight-loss drugs. They’re not. They’re glucose excretion agents with side effects that are literally life-threatening. People think they’re getting a ‘diabetes pill that helps you lose weight.’ No. You’re getting a drug that turns your body into a sugar spill zone. And you’re supposed to be okay with that?

Gary Hattis

November 26, 2025 AT 10:54As someone who’s lived in three countries - US, Japan, and South Africa - I’ve seen how differently this is handled. In Japan, they screen for UTI history like it’s a passport check. In the US? ‘Here’s your prescription, have a nice day.’ In South Africa? They don’t even have access to these drugs. The inequality in care is staggering. We treat diabetes like a tech upgrade - but for millions, it’s a survival game.

And yeah - cranberry works. But so does clean underwear. And drinking water. And not ignoring symptoms. We’ve outsourced responsibility to pills and supplements. Maybe it’s time we took back some of that.

Esperanza Decor

November 27, 2025 AT 06:12I’m a nurse and I’ve seen this too many times. A patient comes in with burning, thinks it’s ‘just stress’ - then it’s a kidney infection. Then sepsis. Then ICU. These drugs are great for the right person - but we’re prescribing them like they’re vitamins. We need mandatory counseling before prescribing. Not just a checkbox on the EHR. Real talk. Real risk. Real consequences.